From “No Bible” to “Know Bible” Part 1: Form Matters

The Bible is a library of books that do things. These books instruct, inspire, reveal, convict, judge, comfort, heal, and save. This means that the Bible is not merely a collection of static words. The Bible is rather a divine speech act.

The Scriptures promise that they contain the power to change things, to actually move the creation in the direction of God’s ultimate purposes for the flourishing of life. For this promise to be fulfilled, however, the Scriptures must be received, understood, and lived on their own terms.

But what does this mean—“to receive the Bible on its own terms”? What does that look like?

Reading and living the Bible well—what we could call dynamic, stellar Bible engagement—happens when a community:

- has good access to a well-translated text presented in its natural literary forms,

- regularly feasts together on whole literary units understood in context,

- understands the overall story of the Bible as centered in Jesus, and

- accepts the invitation to take up its own role in God’s ongoing drama of restoration through the power of the Spirit.

Over the next six editions of this series we’ll be unpacking some of the major elements of this view of Bible engagement in order. Welcome to a whole new Bible, making a whole new kind of difference in our lives.

Form Matters.

The first step in this process involves a paradigm shift in our thinking about the form of the Bible. We’ve all gotten used to seeing and using the Bible in the modern reference book format. For most of us, it’s the only Bible we’ve ever known.

But this format is of course our own creation—something we’ve done to the Bible long after the Bible itself was written. For the first millennium and a half of the Bible’s history there was no chapter-and-verse system laid over top of the text. It was in the sixteenth-century that the Bible was transformed into a standardized, numberized, two-column tool for looking things up.

Rather than reading.

So—no surprise—that’s what we’ve been doing. Using the Bible rather than receiving it. Looking up little pieces of the Bible rather than diving in and immersing ourselves in it. The modern form of the Bible itself tells us to do this. When you see a dictionary, do you sit down with it in a cozy chair and settle in for the evening?

But now imagine this. Imagine seeing the Bible as a library of books that looks like a library of books. Letters that look like letters and stories that read like stories. Nice, comfortable type, set in a single column so there’s no guessing about what is poetry and what is prose. And no additives! No numbers, notes, or nagging distractions. Just well-designed, inviting, easy-to-read, pure text.

Those chapter and verse divisions we added do not reflect the original divisions of the text. They don’t show us Matthew’s five natural sections—a new Torah. They don’t show us the three parts of ancient letters. They don’t show us the parallel structure in Luke–Acts of Jesus journeying to Jerusalem and then the gospel journeying to Rome.

And so on, through all the books in the Bible.

Because here’s the thing: all the books in the library actually have natural literary forms. The Bible’s authors and editors chose particular literary genres to say what they wanted to say. Sometimes they wanted to sing, so they wrote lyrics and set their words to music. The prophets collected their strong, emotional, poetry into stanzas. The apostles used the ancient letter form to instruct distant congregations. Storytellers, well, you know what storytellers do. Because different kinds of writing do different kinds of things well. And the Bible has a lot it wants to do.

This is the literary Bible God inspired.

This is what the Bible actually is.

And our Bibles should show us what the Bible actually is.

So we’ll read it on its own terms, the way it was intended.

We’ve now had a five-hundred-year-old history with the modern reference Bible. The evidence is overwhelming that most people don’t know it. Even people who say they like it often don’t actually read it. Pollster George Gallup was fond of saying the Bible is the best-selling, least-read book in America.

It’s time for a Bible reformation. We can do better by the Bible. It’s trying to be God’s speech act, his living and active word announcing his kingdom and transforming people. Rethinking how we format the Bible can welcome people back into good, deep reading.

The launch of a worldwide Bible reading movement starts with a Bible makeover. It begins with what we see when we look at a Bible. Fresh new Bible presentations embracing the original elegant simplicity of the Bible are the order of the day.

Maybe then the Bible can do more of what it’s trying to do in our lives.

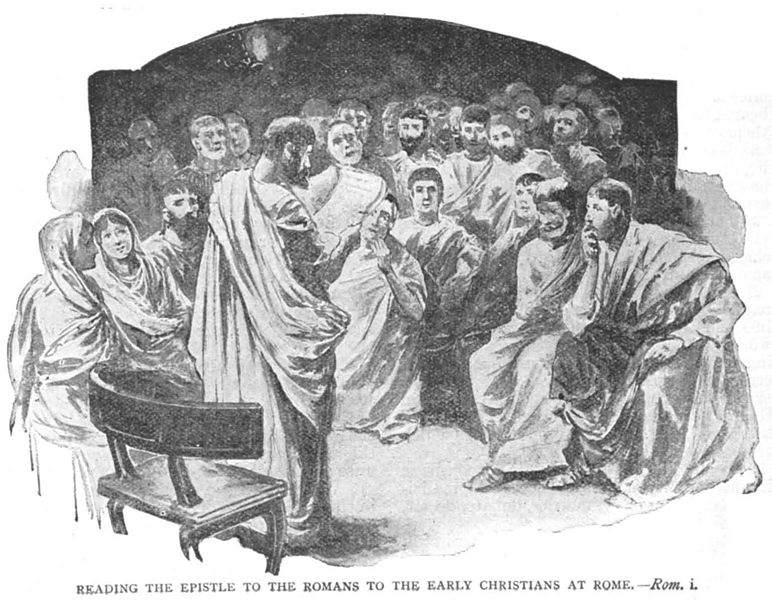

What would happen when a particular local gathering of Christians would receive a new apostolic letter, or even their first copy of one of ancient Israel’s sacred writings? The vast majority of the members of this community would have been illiterate, reflecting this characteristic of the larger Roman world. Yet all the evidence we have suggests that Christian worship gatherings always included a time for the public reading of, and interaction with, these Scripture texts.

What would happen when a particular local gathering of Christians would receive a new apostolic letter, or even their first copy of one of ancient Israel’s sacred writings? The vast majority of the members of this community would have been illiterate, reflecting this characteristic of the larger Roman world. Yet all the evidence we have suggests that Christian worship gatherings always included a time for the public reading of, and interaction with, these Scripture texts.