How the Bible Is Like the Sistine Chapel

In 1508, Michelangelo was commissioned by Pope Julius II to paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. The project – if we can reduce this massive undertaking to a word as small as “project” – took four years and, as we all know, resulted in one of Michelangelo’s most famous works, as well as one of the most stunning and revered works of art in the world.

The painted area of the ceiling measures approximately 131 feet long by 43 feet wide, which means Michelangelo painted over 5000 square feet of frescoes. Nine scenes from Genesis run down the middle, including the famous The Creation of Adam. The border contains depictions of Israel’s prophets, including Jeremiah, Isaiah, and Ezekiel. The scale of Michelangelo’s work is truly monumental.

Of course, Michelangelo didn’t paint these stunning frescoes inside a climate-controlled museum, but inside a functioning chapel. This meant that they were exposed to many harsh elements that made it difficult for the paintings to survive, and practical measures had to be taken to ensure the paintings could be enjoyed by future generations. Linseed oil was applied to the paintings in 1547 to counteract some of the effects of water penetrating through the floor above. Then, in 1713 a layer of varnish was applied to protect them from the soot and grime accumulating from the candles below.

As the years, decades, and centuries passed, the smoke & wax from burning candles and smut from car exhaust fumes built up and made the frescoes so uniformly dark that critics accused the great sculptor of being insensitive to color.

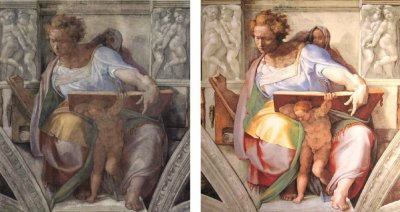

Then, in 1980, a major restoration project was undertaken using modern technology and preservation techniques. They discovered that the layers of varnish and glue that had been applied over the years had hardened and become opaque. Animal fat and vegetable oil had been applied to counteract salination, but had also created a sticky layer that accumulated even more dirt.

So the restorers got scrubbing. They used a variety of different solvents to wash away the layers of dirt, grime, grease, soot, varnish, and exhaust that had accumulated on the original paintings, and what they found was stunning.

“The Fall and Expulsion of Adam and Eve” Before and After

“Daniel” Before and After

When the Sistine Chapel reopened after the restoration, people were shocked at the vividness of the artwork. Michelangelo hadn’t been “insensitive to color” after all. His incredible original work had simply been covered up by years and years of accumulation.

Why am I telling you all of this? Well, it’s a pretty good metaphor for the Bible.

Beginning around the year 1200 when Stephen Langton introduced chapter numbers to the text, and followed by the addition of verse numbers in the mid-1550s by Robert Estienne, modern additives have been accumulating inside our Bibles. Fast forward to today and you’ll see most Bibles come complete with chapters, verses, section headings, footnotes, red-letters, callouts, and cross-references, and all squeezed into two columns so that more information can fit on a single page.

These modern additives, of course, were all put into our Bibles with the best of intentions. Chapters and verses were both added so that referencing small pieces of Scripture became easier (for writing a commentary or concordance, for example). Footnotes undoubtedly showed up because publishers wanted to help people grasp more of the context around what they were reading.

But what has it all amounted to? Information overload. The Bible’s text almost seems hidden, overpowered by all of the extra “helps” we’ve included. Chapters and verses have papered over the natural structures of ancient literature, hiding them behind a uniform numbering system. Two-column formats make it much more difficult to see the parallel structures of Hebrew poetry that we find in the Psalms.

There’s a natural beauty to the Bible that is waiting to be uncovered. If we scrub away the years of varnish and soot, we’ll be surprised and awestruck by what we find. The encouraging trend of “reading Bibles” entering the marketplace shows us that the Bible can indeed be beautiful, and that we can actually have a more authentic, transformative experience with God’s Word if we get rid of all the modern additives and just let the text breathe.