2017: The Year for a Bible Reformation

As you’ve probably heard, 2017 marks the 500th anniversary of the beginning of the Protestant Reformation. On October 31st, we will remember the day 500 years ago when Martin Luther famously posted his Ninety-five Theses to the door of the Castle Church in Wittenburg, Germany. Luther’s Theses strongly condemned some key practices of the medieval Roman Catholic Church, especially the issuing of papal “indulgences.”

The Reformation is certainly a complex topic with a variety of opinions surrounding nearly every aspect of it. But most people will agree that one of its achievements is that it gave the Bible back to the people. The invention of the printing press, coupled with the translation of the Bible from Latin into the common languages, meant that for the first time ever people had access to their own personal Bible. People could read and understand the Bible without having to rely on an intermediary like a priest or church official.

In many ways the Reformation was a necessary and beneficial reorientation for the church. But what’s often missed when discussing the Reformation is the unintended fallout regarding how people view and use the Bible.

For starters, the close historical proximity of the Reformation, the invention of the printing press, and the invention of the chapter and verse numbering system meant that most of the first Bibles made widely available to the public were modern reference Bibles. We’ve written about the pitfalls of this format previously. By 1557, an edition of the Geneva New Testament had indented each individual verse as a separate paragraph. The King James Bible several decades later duplicated this format, and it became the new standard for Bible printing. Today, 500 years later, chapter-and-verse reference Bibles are simply known as “The Bible.”

Second, the proliferation of personal Bibles, along with the Enlightenment emphasis on individualism, led to Bible reading becoming a solo sport. Personal devotions and quiet times dominate the landscape of Bible reading, especially in the West. These things are fine on their own, but what’s been lost over the centuries is the essential practice of reading the text together.

Today there are an estimated 25 million Bibles sold each year in the US alone. The average American home has 4 Bibles. And yet a recent study by the Barna Group shows that the percentage of Americans who describe themselves as “skeptical” of the Bible has more than doubled in the past 5 years, from 10% to 22%. The fastest growing religious category is “no religious affiliation” or “nones.”

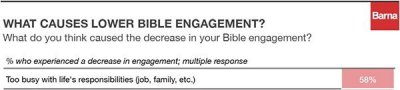

Clearly, something isn’t working within the current Bible paradigm. We have more Bibles than ever, yet its impact on the world seems to be diminishing at an alarming rate. Has the Bible become irrelevant? Can God still speak to us through his written Word today, in the 21st century, when cell phones, emails, Facebook, Twitter, and Netflix grab at our attention nearly every waking hour?

The Bible hasn’t lost one ounce of its power to transform lives, but we’ve found ourselves at a point in history when some necessary corrections are in order. What better time than 2017, half a millennium after Luther’s Theses, to begin a new Reformation around the Bible?

There are things we’ve forgotten about the Bible that it’s time to return to. Reading whole books and natural sections in sequence, for example. Reading with attention to all the different kinds of literature in the Bible. Reading the Bible as a story and finding ourselves within its story, rather than trying to fit little pieces of the Bible into our story. Reading, discussing, and wrestling with Scripture not only in our own church community, but with people from other denominations and backgrounds. The list goes on.

C.S. Lewis once said, “We all want progress, but if you’re on the wrong road, progress means doing an about-turn and walking back to the right road.” We’ve made incredible strides with the Bible in the last few centuries, especially in the areas of translation and distribution. These are things we should be proud of. But we’ve also forgotten some important things about the Bible that need to be restored — we need to backtrack to the “right road.”

2017 can be the year for that. 61% of American adults wish they read the Bible more. 87% of churchgoers say what they want most from their church is help understanding the Bible. The hunger for the Bible is there, people are just tired of essentially being told to try harder in the same old paradigm. The Bible can get back to its work if we just remove the chains that have bound it tighter and tighter all these years. We can move beyond the modern Bible and rediscover the Bible God actually gave us. What better time than now?

In fact, most of my life with the Bible has been constrained by that reference format, leading to the inevitable outcome of lots of study, mastering propositions and doctrine, sword drills around individual verses, ensuring a clear “world view” and so on. Per the definition of literacy, I would say I am actually pretty “literate” when it comes to the Bible. I developed a certain level of competence or knowledge about the Bible, including memorizing lots of verses. And I did it through diligent, personal quiet times.

In fact, most of my life with the Bible has been constrained by that reference format, leading to the inevitable outcome of lots of study, mastering propositions and doctrine, sword drills around individual verses, ensuring a clear “world view” and so on. Per the definition of literacy, I would say I am actually pretty “literate” when it comes to the Bible. I developed a certain level of competence or knowledge about the Bible, including memorizing lots of verses. And I did it through diligent, personal quiet times.