Fasting and Feasting: The Bible’s Story Told by Food

The stuff of earth is the stuff of life—and also the stuff of the biblical story. Trees, mountains, water, and food all figure prominently in the slowly unfolding drama of the Holy Scriptures. Now the fact is, there are lots of prisms for viewing the storyline of the Bible, many built from big theological concepts like covenant and kingdom. But it’s also possible to over-theorize the Bible, turning it into a collection of abstractions. But the Bible itself doesn’t do this. The Bible keeps its story close to the ground, making sure we remember it’s fundamentally a down-to-earth saga.

So, following the lead of the Scriptures themselves, we’ve given you some takes on the big story from the perspective of four earthly elements of redemption. These windows into the Bible’s narrative of renewal are all the stuff of life. We’ve already looked at the story of trees, mountains, and water. And just as with those earlier elements, today we’ll see how food threads the whole story of the Bible. From beginning to end God is talking to us about what we’re eating.

Eating Our Way to Eternal Life

The Bible opens with a poem-like presentation (maybe even a song?) of the creation of the world, complete with refrains of goodness and day counting. Right here at the beginning the Lord is already accounting for food. “Here, see all these plants and produce-laden trees? Those are meals for you, and for all the birds and animals too.” He built food-producing machines right into the fabric of our home.

God didn’t just want us to be. He wanted us to eat to be.

“He gives food to every creature.

His love endures forever.”

Then, in the very next entry in the Bible, food is right there at the center of the story again. This time it’s the trees specifically, but the description is enticing. “Look at them! Overflowing with fresh fruit. Luscious, right? Yes, they’re good for food, so help yourself.”

Adam and Eve, in God’s garden, and the eatin’s good in their new neighborhood.

But there’s also this: “That tree over there, I insist you stay away from it. Don’t eat that, it’s not for you.”

Sadly they ate, and so do we. We seek wisdom apart from God. We try so hard to go our own way. What, exactly, did God really say anyway? It’s unclear, so we’d better decide for ourselves. We have an awful lot of faith in our own perspective, our independent take on things. We’ve assumed a stance of superiority. Aspiring to be God-like, you might say.

And we’ve paid.

The good earth that was meant to be a place that was easy to plant, easy to grow, easy to harvest—this place became dry, hard, sun-baked ground. The gift turned into back-breaking, painful work, all for a little food which was there for the taking at first. So blessing became curse, fruit turned foul, and when we reach for it now, so often it’s only thorns and thistles we come up with.

In the biblical tale this is the ongoing struggle of the present evil age. We need food—real bodily sustenance and solid spiritual nourishment. We’re not necessarily good at getting either on our own, and the creation itself sometimes seems to be working against us.

It’s no accident that eating is at the heart of the biblical story of both creation and fall. Food is so central to life you might even say it is life. In all kinds of ways, we really are what we eat. We are hungry beings—both our hearts and our bodies are longing for everything they need to thrive.

God knows this, of course, so his great, long term restoration project comes with a food plan.

Within the heart of Israel’s sacrificial system is the invitation to feast with God. Bring a food offering to God’s home, light the fire on his altar, and he says repeatedly that the aroma pleases him. At Israel’s birth he invites Moses, Aaron, and the elders to climb the mountain and, believe it or not, to see God and eat and drink. It is a vision, a foretaste, a promise of all that God is working for in this story.

“Come on, let’s eat together,” he says. It’s a way of saying, “Let’s do life together.”

This is why God is so adamant in his Torah instructions that it’s crucial to make sure the poor are fed. Don’t you dare try to sell them food at a profit, or have you forgotten that I’m the one who helped you when you were scraping the bottom of the barrel for leftovers in Egypt? I brought you into this land and gifted you life, so you in turn give your fields a year off and let whoever wants to, grow whatever they want to. Being holy as he is holy includes being generous as he is generous. God himself is the Defender of the fatherless, the widow, the foreigner—so welcome them to share all the gifts of life he’s shared with you.

In the Bible, celebrations of life and God’s good gifts are always times of feasting. God’s gifts are always about building more and better life into his creation. Deep gratitude and joy are the right responses to these gifts, and God tells us the way to express this is in feasting well and good. Scrooginess at feast times is definitely disobedience.

But the flip side of this is equally true. And this is why when things go terribly wrong, the response of God’s people is fasting. To fast is to deny oneself the food of life. It is a way of heightening our own awareness of what’s gone wrong—both in us and around us—and identifying it with dying. The mini-death of fasting is a kind of prayer meant to demonstrate strongly to God the seriousness of both our confession and our supplication. We want the world to change and we want ourselves to change.

Therefore feasting and fasting are both essential to our life in this in-between time the Bible describes. Again and again as the narrative moves on we look to see if a table has been set. Is it time to eat? Or time to refrain?

God joins us in this dual approach to eating. At more than one point he says, “Enough with these sacrifices!” The way we’re acting makes him doubt we really want to share a meal with him. Then again, he always eventually comes back to the dining room, and he’s always rewriting those invitations. “Taste and see that the Lord is good.” He is downright determined to eat with us, and he’ll even dress us up when we need it. He tells us straight up that the only attire for a proper meal with God is the robe of righteousness, the garment of justice. He’ll provide them, but it’s still up to us to credibly wear them.

There’s no question his desire to eat with us runs strong, and we get the feeling as we read along that the banquet is going to win out over the deprivation. Even if we’re unfit for the meal, if we’re found to be less-than-worthy guests, he will overcome even that obstacle.

Whatever it takes, whenever there’s a decent reason, someone’s calling for food.

The ark of God brought to Jerusalem? David shares loaves of bread, and cakes of dates and raisins with the entire assembly. Torah read out loud to the people for the first time in a generation or more? Nehemiah exclaims, “Don’t weep, celebrate! Go enjoy choice food and sweet drinks, and be sure to share with those who don’t have any.”

But even as we read of all these festivities and giant spreads, we know that they are at best temporary reprieves from the daily grind of life in the ancient world, the frequent misery, the devastating destitution. Is this story going to be an ever-revolving tale of feast and famine?

No.

It turns out these earlier refreshments are mere appetizers, foretastes of the real deal meal that’s coming. That greater fare is introduced by a wild man wearing leather and camel hair, surviving on locusts and a little bit o’ honey.

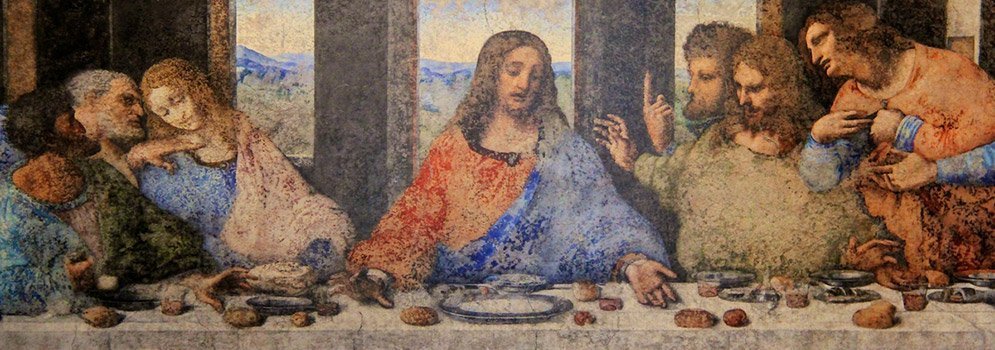

The main course is a Messiah. He says “Yes, you’ve had some manna from heaven before, but I have food you know nothing about, have never experienced. I am here to give you myself, for I am the true bread from heaven. I am the author of life, and I’ve come to be both host and meal for you. Whoever eats this bread will live forever, and not have to worry about famine and fasting ever again.”

The Son of Man came eating and drinking and they called him a glutton and a winebibber, not to mention a friend of all the wrong kind of people. The kind of people who know they are starving, and will welcome a square meal, some fellowship, and a fruit dessert from the tree of life anytime.

This is the wedding supper of the Lamb himself. A feast not just for his people Israel, but for everyone from east and west, north and south, taking their places in the kingdom of God. Those who are last will be first, and the first will be last, and the fast will become feast, forever. Meanwhile, all those who’ve been stuffing their own faces while ignoring the poor will be thrown out.

Wealthy, self-serving Babylon will fall, its prosperous merchants now weeping. But there’s another city, a new city, the Jerusalem of God. It will come down out of heaven to an earth renewed. It’s a city on a hill, with the river of the water of life running right through it. And there, right on this new world beach, someone is cooking for his friends, saying, “Come, have some breakfast with me.” When he takes the bread, gives thanks, and breaks it for us, we’ll know exactly who he is.