Bible reading is what we’ve lost

In 2014 the Center for the Study of Religion and American Culture released the results of a multi-year national study “The Bible in American Life.”* Its purpose was to explore how, where, when, and why Americans use the Bible. The findings included this:

• Less than half of Americans read the Bible outside of a worship service within a year.

• Most of those who did read were looking for specific kinds of help, most often devotional uses, but also insight into topical issues like abortion, marriage, war, poverty, etc.

• Women read more than men (56% to 39%), older people more than younger ones (55% of those over 60 vs. 44% of those under 30); and African-Americans significantly more than other groups (70% vs. 45% or less).

• “Reading” here had a minimalistic meaning of opening the Bible at least one time within the survey year.

Given this research, and the generous use of “reading” for what in many cases was no doubt merely referencing a short passage or even a verse of the day, the conclusion about the amount of Bible reading accomplished is disappointing indeed.

Bible reading is the natural and expected first thing to do with the Bible

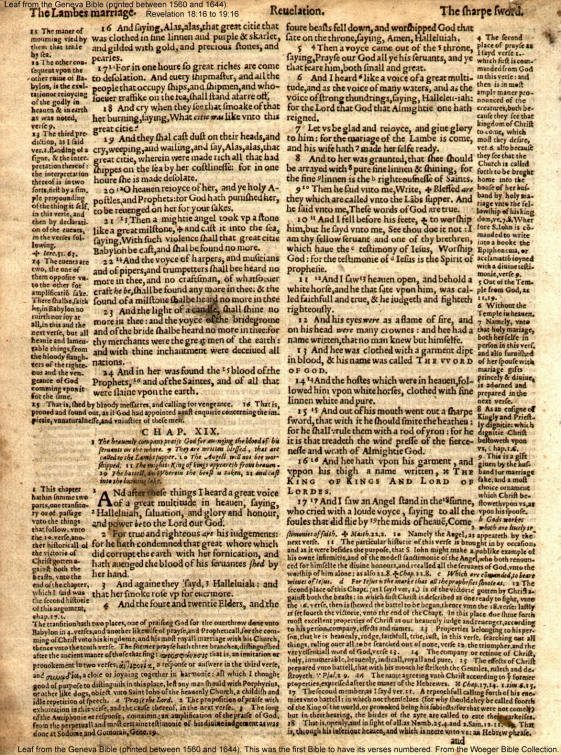

Geneva Bible printed between 1560-1644

Only in modern history did it become possible for large numbers of individuals to read the Bible for themselves. The technology allowing this (the invention of the printing press in the 1450s) was followed within a hundred years by the emergence of the modern reference Bible (the first chapter and verse Bible appeared in the 1550s). The Bible that the masses had available to them was presented in a form that encouraged fragmentary use rather than at-length reading. It shouldn’t surprise us when that is in fact what happened.

But reading the Bible’s books is the most natural thing to do with them.

The oldest approach to reading the Bible is lectio continua—the continuous reading through whole books that occurred when God’s people gathered in the synagogue. The early church continued this practice of deep immersion in the Scriptures. Preachers like Origen, John Chrysostom, Augustine, and others regularly took congregations through complete books.

But in the modern period we’ve become used to the practice of jumping around the Bible to consult small pieces, often taken out of context. Reading big (natural units, especially whole books) is the first step on the path to the recovery of a flourishing Bible.

What Bible reading accomplishes

To consistently read through whole, natural sections is to show our acceptance of the kind of Bible God chose to give us. Feasting on the Bible in this way is to say “Yes” to all the songs, gospels, letters, stories, and wisdom that are the carriers of God’s revelation. It is to say “No” to restricting the Bible to a collection of small-scale pieces of truth for occasional reference.

Ongoing, regular Bible reading provides the best context for Bible study. The smaller, individual parts of the Bible find their true meaning as parts of larger writings. Our learning will be better and our appreciation will be deeper if we have an ever-growing knowledge of whole books.

Ongoing, regular Bible reading provides the only way to gain a rich understanding of the overall biblical narrative. More than anything, the Bible wants to invite us into its story. Big reading is how we accept that invitation and learn how to play our own roles in this gospel drama today.

What does reading the Bible well look like?

Right now, everyone who has a Bible has a presentation of a modern reference edition. But what if it became expected and common for people to own a Bible designed for good reading? What if we expected our Bibles to show the books as the different kinds of writing they are? What if Bible users came to think of at-length Bible reading as the normal thing to do with a Bible?

And then this . . .

• What if Bible readers were equipped to understand the different kinds of writing in the Bible, along with key historical and cultural contexts?

• What if Bible readers operated with a working knowledge of the overall story?

• What if we knew how to read the Bible forward and backward as the Jesus story?

• What if we regularly read the Bible in community?

A renaissance in reading the Bible this way might recapture people’s imaginations, especially younger people (the group losing the most interest in the Bible). Perhaps, once people knew how to read the Bible well, they could also begin to more joyously live it. The road to this full-bodied Bible recovery is found in changing our understanding of what the Bible is, and what we think we’re supposed to do with it.

This is a new path for many of us. But reading the Scriptures whole is the first step. That’s why we’re named the Institute for Bible Reading.

* http://www.raac.iupui.edu/research-projects/bible-american-life/bible-american-life-report/