Why We Should Think Twice About Giving Bibles to Our Friends

About ten years ago a Christian publisher produced a Bible with the evangelistic goal of distributing a million copies. The campaign created lots of “oohs and ahhs” in the Christian community.

But there were issues.  The Bibles, which sold for $1 apiece, were constructed so cheaply they were virtually unreadable. To reduce the page count and save paper costs, it was printed with six columns per spread! So much text was squeezed onto the page that the words ran into the gutter and you had to bend the spine open to read it.

The Bibles, which sold for $1 apiece, were constructed so cheaply they were virtually unreadable. To reduce the page count and save paper costs, it was printed with six columns per spread! So much text was squeezed onto the page that the words ran into the gutter and you had to bend the spine open to read it.

Here’s where the story gets interesting. In 2005, at the height of the campaign, New Orleans was hit by hurricane Katrina. A huge shipment of the Bibles was sent into the devastation.

Not surprisingly, the Bibles were deemed of little value for the hurting masses of New Orleans. But in a moment of brilliance, someone suggested the crates of Bibles could be used for building makeshift dams!

The well-intentioned but infamous “Katrina Bible” is an extreme case of nonsensical Bible publishing and distribution. But it serves as a valuable speed bump to slow us down to re-think our well-worn practice of introducing people to the Bible.

Here are some questions to start us thinking differently:

What is it like to be on the receiving end of a Bible?

What really happens when we give a friend a Bible, specifically a friend without a faith background? We hear the occasional story of someone beaten down by life that providentially stumbles upon a Bible and has a redemptive encounter with God. We love these stories and should rejoice in every one. But what’s never reported, and never will be, are the scores of people who pick up a Bible but can’t make sense of it and lay it down in frustration.

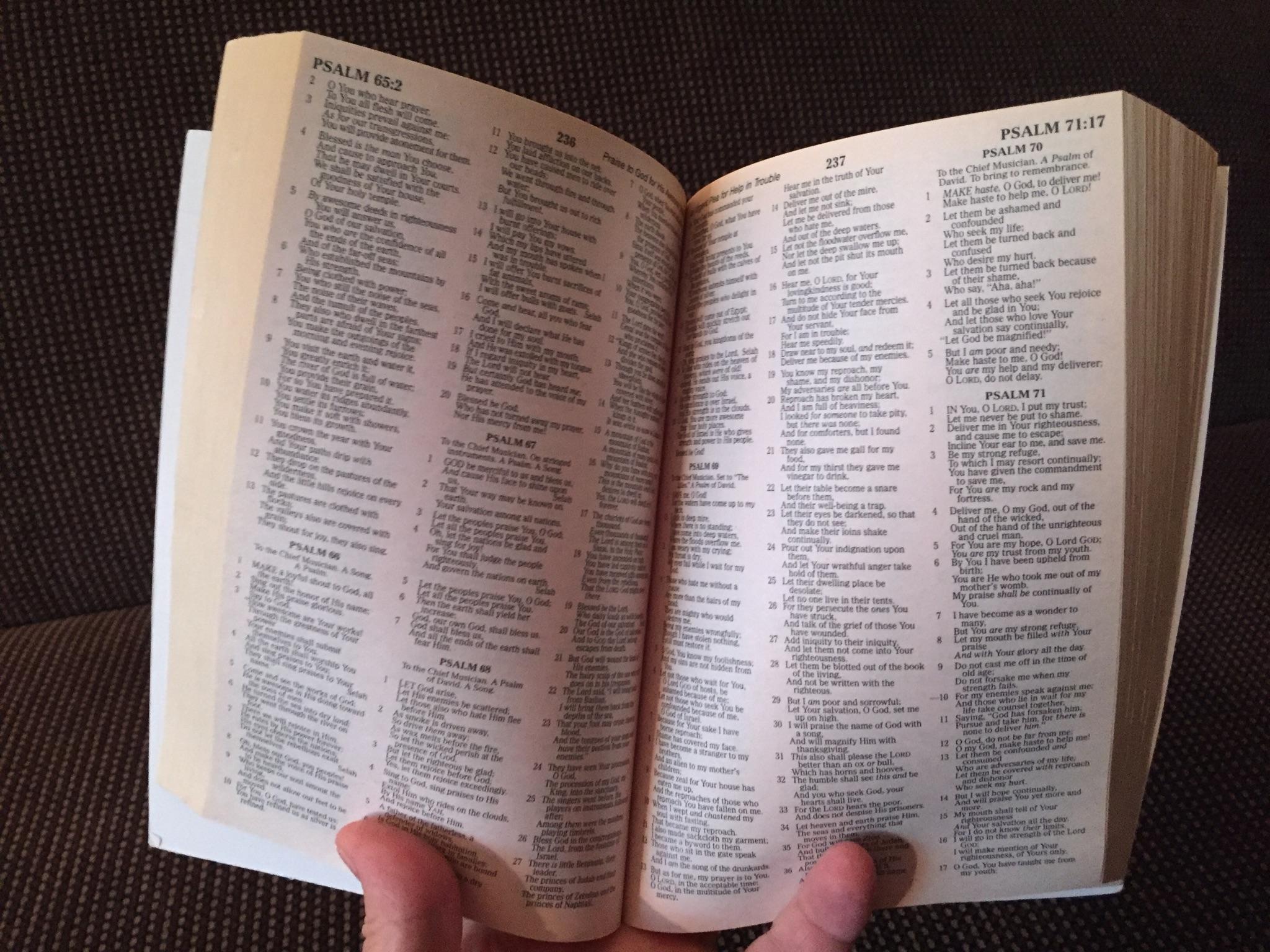

I recently met a new Christian who described the angst he and his wife experienced in their first Bible study. Their frustration began immediately with the Bible itself — chapters (but not like chapters in other books), verse numbers (a completely foreign literary device), and center column references (another literary enigma). The conversations were equally confusing—things were deemed “biblical” because the “Bible said so” in Deuteronomy 5. The Bible was as foreign as the moon to them, but none of the Bible veterans in the group seemed to know or care.

We have to ask: am I giving someone a Bible with the intention of helping them understand it?

Do the Bibles we share communicate the inherent beauty and value of the Scriptures?

When giving Bibles, we should remember that each Bible is a physical artifact, and in essence a work of art.

So what kind of statement do we make when we give cheap paperback Bibles with tiny print, the choice of most evangelistic editions? If “the medium is the message,” what kind of message do we send when Bibles are printed on cheap paper with tiny fonts? When we choose a medium most often associated with cheesy romance novels, what are we saying about our sacred Scriptures? Do the Bibles we give reflect our Creator’s love of beauty?

Do they need a new Bible or a fellow explorer?

The latest data shows that the average North American household owns 4.5 Bibles. Of course, that doesn’t mean everyone has a Bible, or one they can easily read. But if simply owning a Bible were sufficient, we’d be the most spiritually transformed society in the world. We’re not.

The Ethiopian eunuch in Luke’s gospel owned his own Scripture, but he didn’t understand—couldn’t understand—what he was reading. What he needed was a non-threating conversation with a more experienced traveler. How about, rather than giving somebody another Bible and wishing them the best, we sat down and read it with them?

The Bible is still powerful to save!  I believe that. It’s God’s agent sent into the world to transform his creation. But it isn’t automatically powerful.

I believe that. It’s God’s agent sent into the world to transform his creation. But it isn’t automatically powerful.

If the Bible is to flourish in this new era we need to develop a deeper sympathy for the reader.

Bible publishers will have to courageously publish in formats without the confusing additives of the modernist Bible.

Bible advocates will have to give not just a Bible, but give themselves to enter into courteous conversations with the Bible.

To paraphrase E.B. White: The reader is in serious trouble most of the time, floundering in a swamp, and it’s our duty to drain the swamp quickly and get the reader up on dry ground, or at least throw a rope.

Let’s do that with the Bible.