“Eat This Book” – What Eugene Peterson Taught Us About the Bible

Eugene Peterson didn’t give us the Message per se. The Good News itself preceded him.

But Eugene did grace us with a rendering of the Bible that woke us up, causing us to take notice of the startling, disruptive power of these holy words all over again.

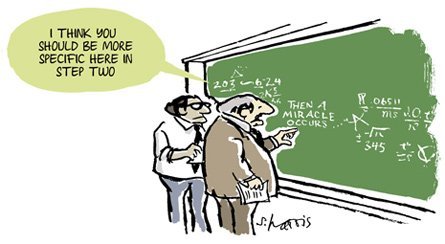

Eugene knew from teaching Sunday School in church that we are all susceptible to the Holy Bible doze. He was teaching Galatians and folks were stirring their coffee, nodding off. He was astounded. Galatians! Paul is so angry he’s swearing, and people are bored and mentally wandering away?

Eugene was like Anne Lamott, reminding us this gospel thing is actually like dynamite, while we come into church and sit calmly, oblivious, worried about wrinkles in our pants. “Hey, hey people! Have you actually read this? Do you get what it says?”

So, yes, The Message was a gift. The God-given words of grace, gracefully written. A presentation of the Bible to make us think again about what we thought we already knew. It helped us feel again what words with power can do. It made the case for the Bible not by arguing for it, but simply by embodying the Scriptures as a speech act—words that do more than stand around shuffling their feet on the page. These were words to accomplish things, executing God’s own actions in us and for us by promising, convicting, healing, and restoring.

Eugene Peterson gave us back the Bible, made fresh.

Eugene Peterson gave us back the Bible, made fresh.

Living and active, fully in the present tense.

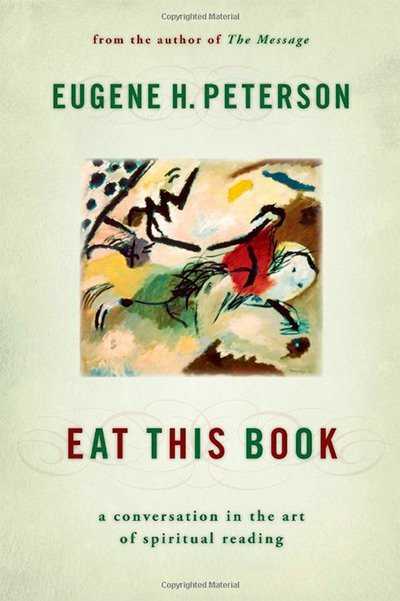

But there’s more. Eugene also wrote about the Bible and our reading of it. The point, he said, is not just to read it, but to read it for living. “What I want to say, countering the devil, is that in order to read the Scriptures adequately and accurately, it is necessary at the same time to live them.” In Eat This Book, which he subtitled A Conversation in the Art of Spiritual Reading, we find all the elements of good reading laid out plain and clear.

Realize what’s at stake, he said:

“The opening page of the Christian text for living, the Bible, tells us that the entire cosmos and every living creature in it are brought into being by words. St. John selects the term ‘Word’ to account, first and last, for what is most characteristic about Jesus, the person at the revealed and revealing center of the Christian story. Language, spoken and written, is the primary means for getting us in on what is, on what God is and is doing.” (3)

and this:

“I want to pull the Christian Scriptures back from the margins of the contemporary imagination where they have been so rudely elbowed by their glamorous competitors, and reestablish them at the center as the text for living the Christian life deeply and well. I want to confront and expose this replacement of the authoritative Bible by the authoritative self.” (17)

Receive the Bible, don’t merely use it, he said:

“C. S. Lewis, in the last book he wrote (An Experiment in Criticism), talked about two kinds of reading, the reading in which we use a book for our own purposes and the reading in which we receive the author’s purposes. The first ensures only bad reading; the second opens the possibility to good reading.” (30)

Read big, not piecemeal, he said:

“Meditation is the aspect of spiritual reading that trains us to read the Scriptures as a connected, coherent whole, not a collection of inspired bits and pieces. . . . What is surprising today is how many people treat the Bible as a collection of Sibylline Oracles, verses or phrases without context or connections. This is nothing less than astonishing. The Scriptures are the revelation of a personal, relational, incarnational God to actual communities of men and women with names in history.” (100-101)

Read it as a story, he said:

“Story is the primary verbal means of bringing God’s word to us. . . . Unfortunately, we live in an age in which story has been pushed from its biblical frontline prominence to a bench on the sidelines and then condescended to as ‘illustration’ or ‘testimony’ or ‘inspiration.’ Our contemporary unbiblical preference, both inside and outside the church, is for information over story.

“. . . Spiritual theology, using Scripture as text, does not present us with a moral code and tell us ‘Live up to this’; nor does it set out a system of doctrine and say, ‘Think like this and you will live well.’ The biblical way is to tell a story and in telling, invite: ‘Live into this—this is what it looks like to be human in this God-made and God-ruled world.’” (40-44)

Enter into the drama, he said:

“As we cultivate a participatory mind-set in relation to our Bibles, we need a complete renovation of our imaginations. We are accustomed to thinking of the biblical world as smaller than the secular world. Tell-tale phrases give us away. We talk of ‘making the Bible relevant to the world,’ as if the world is the fundamental reality and the Bible is something that is going to help it or fix it. . . . What we must never be encouraged to do, although all of us are guilty of it over and over, is to force Scripture to fit our experience. Our experience is too small; it’s like trying to put the ocean into a thimble. What we want is to fit into the world revealed by Scripture, to swim in this vast ocean.” (67-68)

Eugene Peterson gave a good portion of his life’s work to bringing the Bible to us in “American”—in distinctly American language and addressing particularly American ways of misconstruing the world. For him, pastoral work was always local, but we can be thankful that the size of his parish increased over time, benefiting us all. Eugene exerted himself greatly, deploying his love of language and the Scriptures to invite us all back into the bigger, grander, hope-filled world of the Bible.

Rest well in peace, Eugene. We’ll express our gratitude to you properly when we all rise together at the great resurrection.

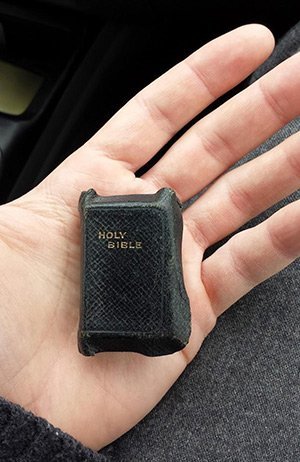

It turns out that electronic Bible providers are employing “a data-centric model” which regularly regurgitates those verses which are already the most tweeted or shared by their user communities. The result is basically a repeating loop of verse of the day Bible balm. This means those who get their Bible online will receive plenty of “I can do all things” (Philippians 4:13) and “I know the plans I have for you” (Jeremiah 29:11), but not so much of the rest of the Bible.

It turns out that electronic Bible providers are employing “a data-centric model” which regularly regurgitates those verses which are already the most tweeted or shared by their user communities. The result is basically a repeating loop of verse of the day Bible balm. This means those who get their Bible online will receive plenty of “I can do all things” (Philippians 4:13) and “I know the plans I have for you” (Jeremiah 29:11), but not so much of the rest of the Bible.

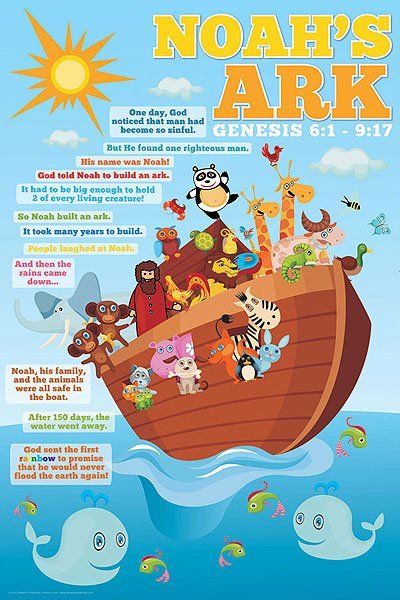

The problem with an ongoing diet of paraphrased Bible stories is that such tellings are not actually the Bible. They are typically told with any age-inappropriate elements toned down or taken out. And of course any paraphrase represents someone’s interpretation of what the essence of a particular story is.

The problem with an ongoing diet of paraphrased Bible stories is that such tellings are not actually the Bible. They are typically told with any age-inappropriate elements toned down or taken out. And of course any paraphrase represents someone’s interpretation of what the essence of a particular story is.